Vatican II - Urgent & Essential

By Arthur Wells & the Editorial Team (written 2005)

"... there [in the Council] we find a sure compass by which to take our bearings in the century now beginning" wrote St John Paul II.

Blessed Pope John XXIII

Elected in 1958, Pope St John XXIII saw the need for an updating of the Catholic Church (aggiornamento) and to seek Christian Unity. He called a Council in 1959, but died before it ended. His death-bed message included: "The moment has come to discern the signs of the times, to seize the opportunity and to look far ahead." Pope John epitomized individual holiness in the Church. Widely experienced, he knew both Church and people's needs. Preparing for the Council, he used homely phrases like opening windows, and that we are not museum-keepers but gardeners to help things grow. He saw the Council as both urgent and essential. Pope John's inspiration, which created a world-wide surge of hope, was completed by his successor Pope St Paul VI. But a small minority—mainly in the Roman Curia—were opposed to the Council from its announcement 50 years ago (25 January 1959) and well beyond its conclusion in 1965.

Pope St Paul VI

Pope St Paul VI's substantial achievement was to steer the Council to a closure albeit with some uncertainties, but eventually with a moral unanimity despite the small minority opposition. He promulgated all its sixteen documents and closed the Council on 8 December 1965. There can be little doubt that Pope Paul was aware of residual opposition and felt it necessary to address the Roman Curia in uncompromising terms:

Whatever were our opinions about the Council's various doctrines before its conclusions were promulgated, today our adherence to the decisions of the Council must be whole hearted and without reserve; it must be willing and prepared to give them the service of our thought, action and conduct. The Council was something very new: not all were prepared to understand and accept it. But now the conciliar doctrine must be seen as belonging to the magisterium of the Church and, indeed, be attributed to the breath of the Holy Spirit. (St Paul VI to the Roman Curia, 23 April, 1966)

Contemporary Circumstances

Many original teachings are becoming obscured partly because there is now limited living memory of the Council and because elements in the Vatican seem to be imposing one-sided interpretations of both Council texts and of the fathers' intentions. It must be asked: can important questions be closed unilaterally while remaining reasonably disputed?

Fifty years on from the Council, an Even Greater Urgency arises

Partly due to the lack of collegiality, the task of promoting Vatican II becomes ever more urgent in the face of internal distortions of Church teaching and ecclesiology. Further unprecedented changes and dangers in the world are occurring. It was inevitable that the Council fathers' intentions could not cope with every eventuality, but would, as it were, set a compass path (cf. Pope St John Paul II above), or be effectively 'the beginning of the beginning' as so many Council fathers, including Butler believed.

The Signs of the Times in the 20th Century

Pope John saw that while the Catholic Church had strong life in certain respects, it had remained somewhat inward-looking and static for 400 years since the Council of Trent. The benefits flowing from the reforms of Trent must be acknowledged, but the catalogue of global changes since the 16th Century is vast and involves greater understanding of the universe, of other cultures and of mankind itself. Pope John saw that the need for reform included first steps to a—perhaps distant—Christian Unity.

What is The Second Vatican Council?

By Roman Catholic reckoning, before the Second Vatican Council there had been twenty General Councils, each called to ascertain the mind of the whole Church on a particular issue. Many hold that 'conciliarity' is fundamental to the health of the Church. Vatican II was such a meeting in Rome. There was no clear-cut plan, but the Council rapidly became a movement for the renewal of the Catholic faith for a new era. It was held in four sessions between 1962 and 1965. Some 2,500 Bishops took part and the Council produced 16 documents. (See Diagram of the Documents). For the broader historical context, see Vatican II - The Historical Context.

Who was Basil Christopher Butler?

Butler was a Benedictine monk, a Scripture scholar, and a distinguished theologian. After a brilliant career in classics and theology at Oxford University and high prospects in the Church of England, he became a Roman Catholic and entered Downside Abbey in 1929. First elected Abbot of Downside in 1946, he was Abbot for twenty years. In 1961 he was elected Abbot-President of the English Benedictine Congregation and was called to Rome to the Council, where he had the privilege of influencing a general Council of the Church in his own lifetime. We are fortunate in having this eminent Council Father as our principal guide for the website (see About Bishop Butler).

Symposium: Abbot Butler and the Council

The Symposium of 2002 is a major section of the website. It marked the twin anniversaries of the centenary of Butler's birth and the fortieth anniversary of the opening of The Council. The Symposium papers were delivered well before the development of a tendency to interpret the Council solely through the texts. The Symposium papers are open, scholarly accounts particularly informed by the rare privilege that two surviving Council Fathers were present and gave invaluable papers. The Archbishop of Westminster, Cardinal Cormac Murphy O'Connor opened proceedings. His Eminence (to whose office Butler himself might well have been appointed in 1963), appreciated Butler's "dry humour and his theological insights, particularly his understanding of the Council."

What grew from Pope St John's Council?

A mood of hope and reform resulted together with a release from earlier narrowness. That narrowness had included the teaching extra ecclesiam nulla salus (outside the church there is no salvation). But the Council steered a new more inclusive and hopeful course, shown throughout the sixteen documents it produced.

Major Documents

Principal among the sixteen are the "Four Foundational Constitutions" from which other documents effectively depend (see diagram). The liturgical changes (Sacrosanctum Concilium) were the first fruits of Vatican II and even forty years later remain its principal association with Vatican II for many Catholics. The Church in the Modern World (Gaudium et Spes) broke important new ground. Butler was not alone in believing that two documents On Revelation (Dei Verbum) and On the Church (Lumen Gentium) contained the most significant of the Church's teachings. These two documents were given the highest 'rank' of Dogmatic Constitution and form the foundation for this website. There were no new dogmas proclaimed and none discarded at Vatican II (see the articles in Vatican II Basics and in the Vatican II in Depth section).

Early growth has not been fostered:

Some essential reforms are being reversed

After great initial hopes and some progress, many key reforms have not been implemented. Among much else, the most basic reform of 'collegiality' in Church governance has not only failed to materialize, but the converse—centralization - has reached unprecedented levels. (See the paragraph below titled A Fundamental Issue... and also see the articles in the Problems and Challenges section.) Because most of the Council fathers' intentions have not been realized, the role of the Roman Curia is examined and the implications of Pope St Paul's address to the Roman Curia quoted more fully above are surely inescapable:

" Whatever were our opinions about the Council's various doctrines before... now the conciliar doctrines must be seen as belonging to the magisterium of the Church, and, indeed, be attributed to the breath of the Holy Spirit."

What is the Magisterium?

The Teaching office in the Church (magisterium) is examined in Governance and also in the Preface to Conscience and Authority.

The Status of Vatican II

The Councils of the 'Modern Era': Trent (1545-63), Vatican I (1869-70) differ from each other and from Vatican II, but the latter is of no less, if not greater, importance. Trent was dominated by the challenge of the Protestant Reformation, but for various reasons, it came too late to heal the breaches. Called by Pope Paul III, with less than thirty bishops initially attending, Trent continued to be plagued in its prolonged duration by church politics under the five popes who reigned in its 18 years duration. Despite interruptions, transfer to Bologna and back again to Trent, it was finally concluded with over 200 bishops by Pius IV in 1563. It produced valuable and overdue reforming work and was the backbone of the 'Counter Reformation'.

Vatican I, for political reasons, was short-lived and is recalled principally for the decree on Papal Infallibility and the skewed ecclesiology which John XXIII believed must be corrected. In calling Vatican II Pope John noted that a Council was not needed to restate Catholic Christian teaching and no Council dealt with it entire. But Vatican II was unique in as far as the Church examined itself and produced an important statement on its nature and function.

The Council provides the most solemn articulation of the Catholic tradition available, until another Council is convoked. Vatican II provides a renewed expression of the faith within the Catholic tradition and is the teaching of the Catholic Church. Aspects of subsequent Synods, which were not fully collegial must also be carefully considered. What matters in the end is the successful achievement of the Council's intentions, wrote Bishop Butler. Should this not happen, he feared increasing irrelevance for the Church. More than forty years after the close of the Council, there is increasing reason for his fear. (See also the paragraph below headed "Bishop Butler on Vatican II, on Reform and Rome" 'whether the fate of the coelacanth was not likely to be the fate of the Catholic Church')

Vatican II: Keeping the Dream Alive (2005)

Archbishop Denis Hurley OMI (see Symposium) wrote a book of the above title. A fellow South African anti-apartheid campaigner, the Dominican Albert Nolan added: How quickly we forget 'there are fewer and fewer Catholics who can remember [Vatican II] when the Church took a giant step forward and what a terrible loss that is proving to be.'

A Fundamental issue: Who leads and governs the Catholic Church?

There is more than one reason for the 'terrible loss' of which Albert Nolan writes. Surely the biggest single cause is that the Vatican has suppressed, neutered or failed to implement several important Council teachings and has increasingly centralized the appointment of bishops. Vatican II taught:

- Every Bishop in communion with 'Peter' is a Vicar of Christ

(Lumen Gentium art. 27). - The Church is governed by all the bishops as successors of the apostles, but always with the Successor of Peter

(cf. Lumen Gentium art. 22). - The primacy of the Bishop of Rome was confirmed.

Thus in regard to the understanding of the Church and its leadership, Vatican II had corrected (in principle) the skewed, uncompleted ecclesiology of Vatican I (1869-70), by recovering 'collegiality', a 'very ancient practice' (cf. Lumen Gentium art.22).

It was the ecclesiology of the early Church and there is no novelty in this key teaching. But the essential reform of collegial government has not been implemented, as is succinctly emphasized in Vatican II of Happy Memory and Hope? Further, the displacing from prominence of the concept of The People of God (notably after the 1985 Extraordinary Synod) is also a displacement of the co-responsibility for the gospel and the Church by all its members (Cf. Co-Responsibility in the Church, Leon-Joseph Cardinal Suenens, Herder & Herder, 1968).

But What is the Church?

By her relationship with Christ, the Church is a kind of sacrament or sign of intimate union with God and of the unity of all humankind. She is also an instrument for the achievement of such union and unity. (Lumen Gentium art. 1)

Study of the whole document "On the Church" (Lumen Gentium), together, in particular, with that on Scripture (Dei Verbum) is essential to understanding Vatican II. In Lumen Gentium the Council produced what is probably the only formal document on the nature of the Church. Earlier discussions had taken place, but by producing the important document Lumen Gentium, Vatican II was unique, although the fathers stopped short of defining 'Church'.

The difficulty in being over-precise is recognized by the Council fathers. The first of the eight chapters of Lumen Gentium was titled: The Mystery of the Church. Of very considerable significance also was, and remains, the title of Chapter II: The People of God. Part of the significance of that title and its placing is that the Church is comprised of all its members. Some members have a particular function as described in The Hierarchical Structure which is the subject of Chapter III. This concept of the Church being all of its members is recovered from the early Church and reflects St Paul (e.g. 1Cor.12). Paul would not have understood the term The Laity, although the fathers were obliged to continue that usage for Chapter IV for want of a better terminology.

How was the Council Taught and Received?

The clear recollection of those old enough to remember is that at the time and afterwards, the Council was barely explained in Catholic churches and it was largely left to individuals to follow it in the press - secular or religious. In Bishop Butler, the London Tablet had an 'insider' reporting, as it were, on issues as they were debated. In UK parishes, the changes to the Liturgy were announced and implemented rather than adequately explained. For how the Council has subsequently been taught and received (or not) by the Church see The Reception of Vatican II.

Understanding the Council as a Development of Doctrine

Pope Benedict referred to a "hermeneutic of discontinuity and rupture", as against a Vatican-perceived straight-forward continuity albeit with some unspecified reform. Nowhere in the opinions of the Council fathers whose work we present can this dichotomy be found, nor is it present in the early writing of the young Fr. Ratzinger- before or immediately after the Council. A change of course does not imply either rupture or discontinuity. Cardinal König, as recently as 2005, noted in Open to God, Open to the World that he was among "those of us who realized that reform was necessary". Vatican II: the Highlight of my Life was his opening chapter. "To my mind, Vatican II set in motion, four really trailblazing, creative and lasting stimuli", he wrote. Can trailblazing mean anything else, as most fathers believed, than a change of course?

The Popes and the Fathers of the Council

Pope John set the tone when opening the Council "The Church should never depart from the sacred treasure of truth inherited from the Fathers. But at the same time she must ever look to the present, to the new conditions and the new forms of life introduced into the modern world". ( ref)

Where is the Church?

A full treatment can be found here. In brief, it is deeply regretted that this remains one of the key questions on which there are many signs that the Vatican is ignoring, or distorting Council teaching. Those among us who were pre-conciliar, 'cradle' Catholics readily recall that being "in the Church" was regarded as essential to salvation: extra ecclesiam nulla salus! Ecclesiam meant the Catholic Church. We continue to belong as adults as a matter of conscience and for more mature reasons than because of circumstances of birth. Much turns on a key phrase in the Document on the Church (Lumen Gentium the subsistit cclause, article 8). Attempts by some circles in the Roman Curia to re-interpret this key phrase drew from a distinguished Dominican scholar: "This disservice to the truth, this denial of the crucial change of course ... must be resisted to the finish." ( Ministry and Authority in the Catholic Church, Edmund Hill OP, 1988, Geoffrey Chapman). Butler and others share that view.

Butler on Vatican II , on Reform and Rome

No one doubts that Butler was unimpeachably loyal to the Roman Catholic Church. But before the Council, Butler had resigned himself to Rome - meaning the Vatican - as a "colossus bestriding the world", which a monk could do little to influence. On learning that a Council was to be called, he recorded: "I feared another dose of authoritarian obscurantism" (A Time to Speak, 1972, p141). In Rome, finding likeminded spirits from around the world, Butler worked tirelessly during all four sessions and in commissions between sessions. Eventually, the forward-looking men won over the vast majority of the members of the Council and many thought of it as a vast educational project, and as a second conversion. After it ended, Butler worked to spread Council teaching. But even after "this miraculous Council", as he called it, he remained concerned that if the Church failed to adapt, it would risk irrelevance like the coelacanth, that living fossil, thought to be extinct until a live specimen was found in 1938. Immediately after the Council Butler wrote:

Catholics believe that the Church cannot perish in virtue of the guaranteed assistance of God [but] the question could have been asked, in the years before Vatican II, whether the fate of the coelacanth was not likely to be the fate of the Catholic Church . (Theology of Vatican II, Rev. Ed. 1981, DLT, p8f)

(For a broader critique from Butler and others see About Bishop Butler.)

Major Theses of this Website

- Vatican Council II is the most important event in Roman Catholic history since the Reformation, and in Butler's opinion, the most important for all Christianity since the great schism between the Churches of East and West in 1054 AD

- Butler was the most distinguished English-speaking contributor at Vatican II and because of his insight remains important for the Church at large and particularly for English-speakers.

- The Council is an ongoing process as stressed by Popes St John and St Paul and as 'a sure compass' by Pope St John Paul II.

- Backward-looking influences at high level in the Church are frustrating reform. Many issues are examined in Problems and Challenges.

Looking Forward with the Word and Spirit of the Council

This website provides access to Vatican II documents and asserts their importance. It also asserts the importance of the spirit, the meaning and the understanding assigned by the fathers to the documents, which they themselves had forged. Doubtless those meanings and not some later glosses are to be preferred. We are a very small group of laymen and women of varying professions, mostly married with grandchildren. The Council generation has an obligation to speak, or the later glosses will be taken as authentic which we believe that they are not. We make available and rely on the intentions of the Council as seen by some of the great men who fashioned it and in particular we rely on the most significant English-speaker at the Council, Abbot later Bishop BC Butler. We hope you will explore the website. It is constructed on the foundation of the Dogmatic Constitution, 'On The Church', Lumen Gentium.

The Editors

Essential Reading

(see also our Select Bibliography for Vatican II)

- The Theology of Vatican II BC Butler (1967, Rev. and enlarged 1981, DLT)

- Letters from Vatican City Etc Xavier Rynne (1962, 63, 64, 65 Faber & Faber)

- The Councils of the Church - A short History Norman P Tanner SJ (2001, Crossroads)

- Open to God, Open to the World Franz Cardinal Koenig (2005, Continuum)

- Rediscovering Vatican II Series Various authors (2005 -08, Paulist Press)

- Ecumenism & Interreligious Dialogue,

Edward Idris Cardinal Cassidy, 2005 - The Church and the World, Norman Tanner SJ, 2005

- The Church in the Making, Richard Gaillerdetz, 2006

- The Laity and Christian Education, Dolores R. Leckey, 2006

- Scripture, Ronald D. Witherup, 2006

- Liturgy, Rita Ferrone, 2007

- Religious Life and Priesthood, Maryanne Confoy RSC, 2008

- Evangelization and Religious Freedom,

Jeffrey Gros & Stephen Bevans, 2009

- Ecumenism & Interreligious Dialogue,

- A Brief History of Vatican II Giuseppe Alberigo (2006, Orbis)

- Theology for Pilgrims Nicholas Lash (2008, DLT)

- VATICAN II Did Anything Happen? Ed. John W. O'Malley SJ; (2007, Continuum) with contributions from Joseph Komonchak, Stephen Schloesser, Neil Ormerod, David Schultenover S.J.

Pope John XXIII reads his opening speech at Vatican II

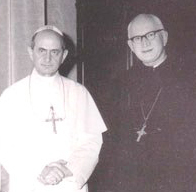

Pope John XXIII reads his opening speech at Vatican II Pope Paul VI with Abbot Christopher Butler, 1965

Pope Paul VI with Abbot Christopher Butler, 1965