Vatican II: the highlight of my life

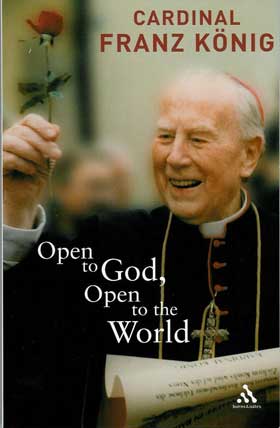

by Cardinal Franz König

The idea of calling a council was conceived by a man at whose election no-one, least of all he himself, had the slightest inkling of the crucial significance he would have for the Church, and indeed for the whole world. John XXIII was and called himself a simple man, a peasant's son,—unprogrammatic perhaps—and yet he called the signals for the Council. He triggered what was to prove a momentous watershed in the Roman Catholic Church. It was he who set in motion that sea change which transformed the Church from a static, authoritarian Church that spoke in monologues, to a dynamic, sisterly Church that promoted dialogue. Himself a man of dialogue, he re-emphasised the importance of dialogue both with the world and within the Church itself.

I saw a lot of Pope John and will never forget his straightforwardness, the cheerfulness with which he approached the arduous tasks that faced him every day and his infectious sense of humour which he always had on tap. The summoning of the Second Vatican Council will always remain linked to the person of this Pope.

In January 1959, while he was still finally making up his mind as to whether he should call a council or not, he seemed at times to be amazed by his own courage. It was soon after he had announced that he was summoning a council that he confided the following to me in a private audience, ' It was during the Octave of Prayer for Christian Unity in January (1959), you know, that, in view of the hurtful separation of the Christian Churches, the idea of summoning a council suddenly came to me. My first thought was that the devil was trying to tempt me. A council at the present time seemed so vast and complicated an undertaking. But the idea kept returning all that week while I was praying. It became more and more compelling and emerged ever more clearly in my mind. In the end I said to myself 'this cannot be the devil, it must be the Holy Ghost inspiring me.' He acted fast, and shortly afterwards, on a visit to San Paolo fuori le Mura on 25 January 1959, he announced that he was summoning a General Council.

It was a bolt out of the blue even for those of us who realised that reform was necessary. I had just been made a cardinal. Together with Cardinal Montini, who later became Paul VI, and several others, I was among the first batch of cardinals Pope John appointed. I remember thinking, 'How will a General Council ever work? Will it deal only with inner-church reform or also with problems that concern the whole of mankind? Will bishops from all over the world ever be able to reach consensus on reform?' In order to understand what was going on in our minds it is perhaps necessary to recall a little what the Church was like before the Council.

I had always had an urge to go out into the world and get to know other countries, other religions. On a visit to England as a young curate in the 30s, I remember being fascinated by the different Christian Churches and beliefs. Unlike in Austria, where almost everyone was Catholic, here one encountered Anglicans, Baptists, Methodists, Quakers etc. I was staying with a Roman Catholic parish priest in southern England when I discovered that there was a convent of Anglican nuns nearby. When I told my host that I wanted to pay the nuns a visit, his immediate reaction was, 'No, no. You must be careful. That might be seen as encouraging ecumenism'. 'All right', I thought sadly, 'but why – or rather why not?' The priest's reaction was typical. The Roman Catholic Church feared ecumenism. Later, on my pastoral visits as a bishop, I soon became aware that many Catholics found it hard to accept the denunciation of non-Catholics and longed for a change in the Church's stance on ecumenism. Many of them were married to non-Catholics or worked together with them in the same concerns. And although there was already a strong ecumenical movement outside the Roman Catholic Church, we Catholics were discouraged from taking part and were not supposed to go to ecumenical meetings or discussions on the subject. We were in a fortress, the windows and gates of which were closed. The world was out there and we were inside, and yet we were supposed to go out and take the Gospel Message to all nations. But although we often shook our heads, we accepted the status quo and all those rules and regulations. And we had absolutely no inkling of how those walls could be removed.

Soon after the Council was announced, I heard that every Council Father could take a theological advisor, a so-called peritus, to the Council with him. I immediately rang Father Karl Rahner, a Jesuit whom I knew well, and asked him to accompany me to Rome. I wanted a theologian who would help me to get a better grasp of the overall connections but also to present the faith, that is the Christian Weltanschauung, in such a way that it moved people today and did not pass them by. I knew that Rahner was convinced that our mission was not to keep the faith locked away behind closed doors, but to go out into the world and proclaim the Gospel Message. When I asked to accompany me, however, Rahner was aghast. 'What are you thinking of ?, he said, 'Rome has considerable misgivings about me and my writings already. Imagine what they would say if I turned up as a council theologian!' And with that he declined. I asked him to think about it and said I would ring again later. When I did, Rahner said, 'All right, in God's name, but you must take the responsibility! Who knows what will happen when Ottaviani sees me!' I had already got to know Cardinal Ottaviani, the head of the Holy Office, as the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith was still called then, under Pope Pius XII. I remember bumping into him once soon after Pius XII first allowed evening Masses. He came up to me and said, 'Have you heard the latest? We may now celebrate Mass in the evening. Don't people laugh when you announce an evening Mass?' It took me a little time to see what he meant, but it was a typical Ottaviani reaction. There is a fixed order of things which must never on any account be changed, - semper idem (always the same) was after all his motto, - and as change was inconceivable, it was also in a strange way ludicrous! I was, therefore, somewhat worried about what Ottaviani would say to my bringing Rahner. So on my next visit to Rome I informed him privately. 'Rahner', he muttered, shaking his head, 'How will that work?' He wasn't against it, just worried. Not long after the actual Council had begun, however, I saw Ottaviani and Rahner strutting up and down St Peter's together deeply absorbed in conversation. Ottaviani was against change, but he was far more flexible than his right hand, Fr Sebastian Tromp, an ultra-conservative Dutch Jesuit, whom I knew well as he had been one of my teachers at the Gregorian. Tromp was utterly convinced that the Church was the Mystical Body of Christ and as such the absolute apogee of theology after which there could simply be nothing new. He sometimes quite unexpectedly came o visit me in Vienna. Perhaps he thought he could 'convert' me to his way of thinking.

Rahner scanned the numerous drafts and propositions that were sent out in the preparatory phase of the Council for me and was sometimes highly critical. 'The authors of this text have quite obviously never experienced the suffering a distraught atheist or non-Christian experiences who wants to believe and thinks he cannot', he once commented. And on another occasion he said, 'These drafts are the elaborate theses of comfortable, self-assured churchmen who are confusing self-confidence with firmness of faith. They are the theses of good and pious scholars, selfless - but simply not up to today's situation.' But there were, of course, texts that Rahner approved of.

I will never forget the opening day of the Council. As the relatively young Archbishop of Vienna, I proceeded with two and a half thousand other bishops down the Scala Regio towards the entrance of St Peter's. As I looked around me I realised for the first time that the Church was a global Church, an impression that has remained indelibly impressed on my mind. The Pope was carried into the basilica, but then got down from his portable throne and walked down the aisle between the rows of bishops. He was not wearing the papal tiara, but an ordinary mitre like the other Council Fathers. And then came his pathbreaking address in which he bade the bishops not to listen to the 'prophets of doom', but to tackle present-day problems joyously and without fear. As I looked around me I saw that all the tension and scepticism had given way to joyous surprise.

I have often been asked which I think are the Council's most important achievements. To my mind Vatican II set in motion four really trailblazing, creative and lasting stimuli. First it established the Church's universality. At the Council Sessions, and above all during the discussions in the intervals, one could see bishops of every colour and nationality in lively debate speaking many different languages. This multitude of different nationalities, languages and cultures changed the awareness of the Council. The Church laid aside its European attire, which many of us were so familiar with, and some even identified with the Church itself, and became aware that it was a global Church. That is why Latin could no longer be the universal language of the liturgy, and the vernacular was introduced.

The second breakthrough which opened the walls was the Council's support for ecumenism. It was Pope John himself who courageously took up the delicate issue of ecumenism. He had spent years in Turkey and Bulgaria and had good contacts to the Orthodox and Old Oriental Churches. The initial decision to invite non-Catholic observers to the Council came from him. Soon after Easter in 1960, he took an indicative and most significant step. He set up the Secretariat for Christian Unity, a small but high-powered body, to handle ecumenical matters, and appointed Cardinal Bea, an eminent scripture scholar and rector of the Biblical Institute in Rome, its president. Bea's role at the Council cannot be rated highly enough. The very first draft for the decree on ecumenism already went into the highly controversial subject of inter-religious dialogue, for instance, but this was later taken out and became a separate declaration. Bea and his secretariat took over the responsibility for inviting and looking after the observers, who were by no means passive, as their designation might suggest, but played an increasingly influential role at the Council. Most of them were non-Catholic Christians. They had eye-contact with the cardinals as they sat directly opposite them in St Peter's, and although they could not speak at the sessions, they took an active part in the numerous discussion groups and conferences that took place during coffee breaks and after the session debates. At the beginning there were about 40 observers but by the end of the Council there must have been close to 100. They immediately had a positive influence on the ecumenical climate and their role grew as the Council progressed. They got to know many of the Council Fathers, council documents went through their hands and their opinion was sought and valued. They were also able to rectify misunderstandings and bring in new aspects, and their opinions found their way into several council decrees. This was ecumenism at work and it was first and foremost Cardinal Bea's achievement. I myself had frequent discussions with several of the observers and we often found ourselves in agreement on fundamental matters of faith, even if the actual formulation or wording was different. Already after the first session, in 1963, Lucas Vischer, a Lutheran member of the World Council of Churches with whom I had frequent discussions, compared what was happening at the Council to the 'bursting of a dam'. And I knew Oscar Cullman, Protestant Professor of New Testament Studies at Basle and Paris, well. After the Council was over, he said, 'Looking back and considering the Council as a whole, our expectations, except in a very few cases and in so far as they were not illusions were fulfilled and even surpassed on many points.' Another leading Lutheran theologian who attended all the Council sessions as an official observer was Edmund Schlink. Schlink was professor of ecumenical theology at Heidelberg University and a leading member of the commission on Faith and Order of the World Council of Churches. He was a keen ecumenist and very outspoken. One of his interviews for the German press in September 1963 during the second session of the Council caused quite a rumpus. In it he sharply criticised that in one of the documents under discussion the Church of God was being exclusively interpreted as the Roman Catholic Church. This insinuated that the yearning for Christian unity was the wish to return to the Roman Church under the Pope and sounded as though Orthodox and Protestant Christians were to be persuaded to leave their church communities and return to Rome, he emphasised. But Schlink greatly admired Pope John and Cardinal Bea. When Bea died, Schlink wrote, 'The death of Cardinal Bea is a great loss, not only for the Catholic Church but for the whole of Christianity. He will be mourned by all people of good will… this humble and fatherly man reconciled the Christian Churches and convinced them that the Catholic Church's new ecumenical orientation was genuine.' Such praise for a Roman Catholic cardinal from an eminent Protestant theologian was remarkable. Schlink also had an almost uncanny capacity for understanding the problem of papal primacy. He wrote a delightful book called 'The Vision of the Pope' which is a fictional account of a Pope's inner struggle to carry out his office as the head of the Christian Church in the way Christ would have wished him to. I re-read it when I was asked to write the preface to the second edition a few years ago and was astounded how relevant it is to the situation we are confronted with as regards the papacy today. Vitali Borovoi, one of the observers from the Russian Orthodox Patriarchate, was another enthusiastic supporter of Vatican II who wrote, 'Both John XXIII and Paul VI were authentically 'angelic popes' (pastores angelici), to use the terminology of medieval prophecy. They dedicated their lives to the great work of the renewal of the Catholic Church, for Christian unity and the affirmation of the peace and brotherhood of peoples all over the world.'

The third important breakthrough, which in my eyes was of particular momentum for the future of the Church, is the Council's emphasis on the importance of the lay apostolate. Before Vatican II the Church was often perceived as a kind of two-class system with the hierarchy on one side and the laity on the other. This was a view that in part corresponded to the social structure of society at the time which sharply differentiated between those who ruled and those who were ruled. But that was hardly the Gospel view. Vatican II stated quite clearly that the Church is one communion. All of us, that is all the baptised, are the pilgrim People of God and we all share the responsibility for the Church. It is becoming ever clearer how important cooperation between priests and lay people is, but also how important the lay apostolate in itself is for the future of the Church.

I have already gone into Nostra Aetate, the Declaration on the Relation of the Church to Non-Christian Religions, in detail in other chapters of this book but would like yet again to emphasise how important this briefest of all the Council's declarations was and is. The Church's relations with Judaism, Islam and the other world religions have become more important than ever in the third millennium and if we are to avoid the clash of civilizations that Samuel Huntingdon prophesied, everything must be done to promote inter-faith dialogue.

For many, however, both inside and outside the Church, the renewal of the liturgy was the Council's most striking reform. Misunderstandings arose because the change was too abrupt and the faithful were not prepared gently enough. Many Catholics were so deeply attached to the liturgical forms they had grown up with and had been familiar with all their lives that the fact that the liturgy was now no longer in Latin but in the vernacular, and that the priest faced the faithful etc. was almost more than they could cope with. Elderly priests found these changes particularly difficult. I still remember the despairing look in the eyes of one very old parish priest who, when I arrived to visit his parish, came up to me before Mass and said with a catch in his voice, ' I've tried, your eminence, I really have, but I just can't, I'm afraid' (I told him not to worry.) And yet there have been many such changes throughout the Church's history. The Greek-Catholic Churches, moreover, who are in full communion with Rome, have never used Latin. Besides, Vatican II did not ban Latin, it merely allowed the vernacular. As far as the liturgy is concerned, we should neither overrate the new forms nor place too little value on the old forms.

A great deal has been written about the Second Vatican Council over the last forty years and I think I have probably read most of the better-known works on the Council. One of the aspects that has often been underrated, however, is the role played by committed journalists who informed the world of what was happening at the Council. The Council Fathers would never have been able to focus the world's attention on this phenomenal event without the cooperation of the media.

The Church was slow to realise the importance of the media and to recognize its true value. Already in the 30s, the English historian of Vatican I, Abbot Cuthbert Butler, strongly recommended that at future church councils journalists should be allowed to attend the debates so that they could report what was being discussed. Butler was convinced that the mistrust, scorn and derision Vatican I had earned was due to the lack of precise information at the time. And at the International Catholic Press Conference in 1950 Pius XII criticised the lack of communication between the Church and public opinion, calling it 'a mistake, a weakness and a malady' and saying that both the clergy and the faithful were to blame. But little changed. Until Vatican II, the general policy was to let as little as possible of what was going on in the Vatican leak to the outside world.

This time, however, all endeavours to keep the Council debates secret were soon dropped, which in itself was already a sign that the Church's attitude had changed. It rapidly became clear that any attempt to hold the debates behind closed doors would have poisoned the atmosphere and given way to rumour and speculation. From then on everything that happened at the Council was reported. I myself was convinced that if the Council was to be a success, it was crucial for able and committed journalists to inform the faithful and the world of what the hierarchy was discussing. Well before the Council began, I therefore told Catholic journalists in Vienna that once it started, they should not wait to ask their bishops, but should inform the world of what was being said at the Council and not hesitate to criticise or press for answers whenever they thought it necessary. It was their duty, in the interest of both parties, to get the Church and the world to engage in dialogue. I also encouraged them to write about what ordinary people, especially the Catholic faithful, expected of the Council so that what began as a hope would not end in disappointment.

I am certain that the decision to inform the world of what was being debated at the Council set an excellent example. The fact that the entire Roman Catholic hierarchy and more than a hundred observers from other Christian denominations had gathered in Rome to review crucial spiritual issues in all openness at a time when the world seemed solely engaged in political or wordly matters, (the council convened from September 1962 – December 1965, at the height of the Cold War) was seen as a positive signal. The world realised the far-reaching implications and gave a nod of assent. The way in which public opinion propagated the Council exceeded all forecasts. Accomplished and committed journalists like Mario von Galli of the Swiss journal Orientierung, who covered the Council for the German speaking world, Peter Hebblethwaite of the English Jesuit journal The Month and Robert Blair Kaiser of Time Magazine, to mention only three, connected the Aula of St Peter's with the outside world and 'transcribed' the topics that were being discussed, the debates that ensued and the often seemingly endless proposals and amendments into a language that the world could understand. This not only required an exceptionably observant eye and the ability to grasp overall connections quickly, but also a gift for asking the Church and the World the right questions at the right time and then commenting critically. It takes immense patience to accomplish such a feat but also a great sense of humour and the journalists concerned did a wonderful job. For over three years the Council was prime news worldwide, much of it positive. Even the Ecumenical Patriarchate's official newspaper, Apostolos Andreas, was full of praise, and the Greek Orthodox Church's newspaper, Ecclesia, wrote, 'At this Council the Catholic Church has shown that it is a different Church from the one we have known up to now.'

We connect the splendour and the glory of the Council with Pope John, but the spadework was left to Paul VI. He had to shoulder the burden of Vatican II. I think future generations will come to a more just appraisal of Paul VI's role at the Council and appreciation of what he did will grow. For me he was the martyr of Vatican II. The death of Pope John in June 1963 left the Council in a precarious position. What would happen now? Who would succeed Pope John? And would whoever succeeded him proceed with the Council or break it off? All the Council Fathers and with them the entire Church waited in trepidation. My very modest room at the conclave was next to that of Cardinal Montini of Milan. On the very first day of the Council it soon became clear which way the wind was blowing and that Montini would be elected. That night he looked so downcast that I decided to drop in on him. When I told him that I, too, shared the general view that he would be elected the next day and was overjoyed, he kept trying to convince me that I was wrong. As we said goodnight he said, 'I am enveloped by complete darkness and can only hope that the dear Lord will lead me out.' When he was elected the next day, I feared he would say 'No', as has repeatedly happened at conclaves. But Montini said 'Yes' albeit very hesitantly. He did not want to become Pope. From that moment on, however, it was more or less clear that the Council would go on. A few days later Paul VI declared his intention of continuing the Council along the lines that Pope John had conceived. Paul VI greatly admired his predecessor. He had not spoken much during the first session of the Council but the little he had said showed that he was fully in favour of church renewal. Although he did not convoke the council or begin the reform process, he continued it and saw it through. This was not easy, especially for someone who, unlike John XXIII, did not have the charm to stir people with a single smile. But Paul VI had the tenacity, perseverance and will power to soldier on. And he also had that strength which comes from great humility to step back and make himself small when faced with an overwhelming task. The great work of church renewal, however faltering, hesitant, inhibited and obstructed it may sometimes seem to us, would have crumbled if he had not persevered. The Council proceeded, albeit with small, faltering steps, - and at times it even came to a standstill, - but there was no change in direction and the aim was never lost sight of. Pope Paul picked up what his predecessor had triggered and translated it into action.

I will never forget the solemn ecumenical service in St Peter's on 7 December 1965 which marked the end of the council. I was one of a small group on the altar with Pope Paul VI. After asking the representative of the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople to join him there, the Pope announced that the Papal Bull of 1054, which had declared the Great Schism between the Western and Eastern Church, was now null and void. I can still hear the thundering burst of spontaneous applause with which his announcement was greeted and many of those present had tears in their eyes. For me this highlight signalled that the impulses set off by the Council were already at work. The crucial process of reception, that all-important part of any church council, which can take two generations and more, had begun.

The text on this webpage is Chapter 1 of Open to God, Open to the World, by Cardinal Franz König, edited by Christa Pongratz-Lippitt, Burns & Oates, London, 2005, and is reproduced with permission.