Bishop Christopher Butler,

Seventh Abbot of Downside and Bishop of Nova Barbara

by Dom Daniel Rees OSB

A LISTENER to one of Abbot Christopher Butler's conferences to the monastic community expressed his admiration for the Abbot's skill in rising to St Benedict's requirement 'that he should have a treasure of knowledge whence he may bring forth things new and old', ut sciat at sit unde proferat nova et vetera. That appreciation is capable of a much wider application - to his whole life and work. He was always seeking to bring together in a fruitful interchange whatever patrimony he had assimilated and whatever raw discoveries confronted him, confident that ultimately they could be successfully harmonized. In this, as in so much else, he exhaled the spirit of Cardinal Newman.

No one could have been more thoroughly English. In a negative way this made itself manifest in the decidedly expatriate demeanour which descended on him whenever he was outside his native context. But it could also be seen in his preference for the simple pleasures of private life - his armchair, his pipe and detective novel, in his unfailing courtesy and again in the philosophical goodhumour with which he greeted whatever was tiresome. And perhaps no other part of the country could have delivered this character so well as Reading, his birthplace in 1902, There the Englishry is not overlaid by any pronounced regional features. It is near the centre, but at a slight distance.

He was third in seniority among six children, the inconspicuous place he would himself have chosen. His father was engaged in the family's wine and spirits business, established at Reading in 1830. At the age of 3 the future bishop was discovered reading Dickens which he had climbed to take down from the top shelf of the bookcase. At the age of 9, his teacher at the local elementary school made strong representations to his father that the boy try already for one of the four scholarships annually awarded by Reading School, even though the normal age of entry was 11. Needless to say, he carried it off, as would be the case with every examination he took until his driving-test, and for the next decade he progressed through Reading School always two years ahead of his contemporaries. With his very logical cast of mind he could have excelled at Mathematics - the square root of minus one was a matter of lifelong absorbing interest - but he also revealed early a feeling for words and the constructions that could be made of them, and opted instead for Classics. His intellectual zest was entirely spontaneous; no driving parents nor any enlivening teacher was at the root of it.

In 1920, he went up to St John's College, Oxford, on a scholarship - the only way in which the University would have been open to him. He once described his Oxford career as 'undramatic'. In a sense, it was. One after another the trophies fell to him - the Craven Scholarship, the Gaisford Greek Prose Prize, proxime accessit in the Hertford Scholarship. He refrained from competing for the Ireland Scholarship in order not to imperil the chances of a friend. His triple First, in Mods, Greats and Theology, he took well in his stride. Like his old school, St John's won a permanent place in his affections and few distinctions gave him greater pleasure than his old college's later award of an Honorary Fellowship. In 1925, he became a tutor in theology at Keble, and in 1926, he was ordained a deacon in the Church of England.

At this time, in spite of an intellectual liberalism, he was an uncompromising High Churchman, not in any flamboyant sense, but as one who took church order and church discipline very seriously. But unlike Ronald Knox and Robert Hugh Benson he had not come across Anglo-Catholicism as an exciting discovery of his own; it was his family allegiance. Those post-war years too were a time when the Anglo-Catholics were reaching the zenith of their influence and seemed poised to take possession of the Church of England. The chief manifestation of their triumphalism was a series of Anglo-Catholic Congresses held at the Albert Hall, and there, in 1927, the youthful Mr Butler delivered a paper on 'Christianity and the Mystery Religions'. Many hopes were set upon him.

Throughout his life he set out to be an apologist, but one who always patiently followed stage by stage the arguments of his opponent. The chief contemporary onslaught on the uniqueness of Christianity came from the School of the History of Religions whose leaders were Bousset and Reitzenstein. Butler decided to spend the vacation in Germany and study their works. This was one of his rare forays abroad, and he found it a revelation that in the Black Forest the whole population, and not just those with ecclesiastical tastes, turned out for Mass quite naturally, as a worshipping community. This was for him the counterpart of Augustine's phrase that so haunted Newman, Securus iudicat orbis terrarum, and seemed nearer than anything he had previously experienced to his vision of the Church as wide as humanity itself. Not long afterwards, back in Oxford, he was sallying forth one Sunday in cassock and biretta to officiate at one of the city's many temples when he was accosted by a working man who asked, 'Where can I get Mass, Father?' And he realized that the only honest answer would be to direct him to St Aloysius's. His life-long friend, Martin Hancock, a younger undergraduate at St John's, was simultaneously coming to believe that a Church whose unity was visible was an essential element in God's plan of salvation. They went for a walk together on Cumnor Hill to thrash out their predicament. Absorbed in their talk, they sat down on a barrel beside the road. When they came to go, they found they were stuck; the barrel contained tar.

In 1927, on the recommendation of Doctor Kidd, the Warden of Keble, who knew of Downside through his friend Armitage Robinson, Dean of Wells, Butler came to see Abbot Ramsay to talk over his position. He resigned his post at Oxford and went to teach at Brighton College. In 1928, he returned to Downside to become a laymaster. He had just been received into the Catholic Church. His conversion was out of a sense of duty rather than from enthusiasm. He retained a strong attachment, even one might say a preference, for the ethos of the Church of England, and he knew the grief the move would cause to his close-knit family. But he held that logic made the Catholic case the only tenable one, and he felt he had a moral obligation to take the step he did. But he did bring into Catholicism a sense of the local church and a great many other values from Anglicanism, which one day would come to full expression. Not least among these was his very powerful conscience which was almost palpable to all who came within its range.

He could not help comparing the boys he taught at Downside with those he had known at Brighton College, and he observed that while the Gregorians were perceptibly more intelligent, they lacked the zest for investigating ultimate questions, the thrill of the search, which he had been able to engender among his former pupils. He attributed this to their conviction that they already had the answers. After only a year in the lay state he entered the monastery. Soon he was teaching Classics in the School again under Neville Watts, from 1933 to 1940, the period which probably gave him most pleasure in all his Downside career. The communication of intellectual appreciation was always for him such a sheer joy that his face began to beam and one could almost hear him gurgling. He got great happiness too from being in charge of the Top Dormitory where every night he would read to the boys from The Wind in the Willows or The Bridge of San Luis Rey, a novel that particularly impressed him because all the characters seemed to die at what turned out to be for each of them exactly the right time.

It was during this stage of his life that he got caught up in two engrossing movements. Together with the Earl of Lytton he founded the League of Christ the King to help young men in the public schools, the universities and the professional world live out their faith. Its motto was Pro eis sanctifico meipsum and it reflected very much his own personal spirituality. It flourished for the next thirty years. He was also very much to the fore in the movement at Downside, led by Dom David Knowles, to make a foundation where the life would be more contemplative. The overriding purpose of a monastery was always for him the advancement of its members in their personal prayer. Its liturgical, social and apostolic operations were for him almost incidental. And in his spiritual life his chief master was de Caussade. As a boy he had been asked by the vicar to make himself responsible for replenishing the lamp before the Reserved Sacrament when he cycled past the church daily on his way from school, and it was to this undertaking that he traced his initiation into the practice of regular prayer.

From 1940 to 1946 he was Head Master. In his own life this was rather a strange turn of events because his own parents had firmly held objections in principle to boarding schools and had declined to send one of his brothers to Christ's Hospital when a place was offered him. Their attitude sprang from their very strong sense of family which he himself had inherited; throughout his life he never allowed a family occasion to pass by unnoticed. He had even taken the name 'Christopher' because of some family connection. His belief in the responsibilities of parents led him to propound the merits of 'school vouchers' long before the notion was taken up by politicians.

His regime almost coincided with the War [1939-45], and he had to eke a place in Downside for two other evacuated schools: the Preparatory School from Worth occupied the just-completed Caverel-Barlow Block; the Oratory took over some of the present Junior House accommodation. It was not easy in those years to find suitable teachers because all the men who were fit were in military service, and not a few of the monks were also chaplains in the forces. He did not have the talent for masterly organization and coups de théâtre which was possessed by his abbot and by many of his housemasters who then included several future headmasters. He had no relish for running things; his hopes were rather set on communicating to his boys the Christian spirit and the love of truth, moral and intellectual. And that he possessed what he stood for became crystal clear to everyone in June 1943 at the aeroplane crash when he comforted the parents of the victims and strengthened by his calm the will of the whole School to resume life as normally, one day after the tragedy. He could remember the Christian names of every single boy when he shook hands with them all after the evening assembly, and he managed to have a private conference with every one of them at least twice a year. During his headmastership the numbers rose by more than a third, as also did the academic successes, beginning a movement which would gather pace under his successor.

In 1946, he began the first of his three terms of office as Abbot. Although no one would describe him as a man of action who went out to meet trouble half-way, nevertheless many momentous achievements mark his incumbency. Ealing and Worth became first priories, then abbeys in their own right. The movement towards Ealing's independence had been almost completed before he took over, but when the time was ripe for letting Worth stand on its own feet, he took infinite pains and consultations to ensure that it would have the best possible start, and he was particularly generous in giving the fledgling community its share of the young and vigorous men available. He did not believe in denying self-determination to a daughter-house for longer than was necessary - a practical instance of his instinct towards subsidiarity which was also shown, for better or for worse, in his giving their own head to all his officials. He had no wish to be a court of first instance, and this detachment gave him time to write his most scholarly books. In 1951, he published his arguments for the Matthaean priority in The Originality of St Matthew. With some variations his view had already been held by Abbot Chapman, and was afterwards championed by Dom Bernard Orchard and Dom Gregory Murray. (This strange coincidence led a monk of another house to ask if Gregorians took a fourth vow to uphold this solution of the Synoptic Problem.) In 1954, he produced The Church and lnfallibility, a rejoinder to the erudite attack on Catholic claims by Doctor George Salmon, a Provost of Trinity College, Dublin, in Victorian times, which had just been reprinted with the advertisement, 'Unanswered because unanswerable'.

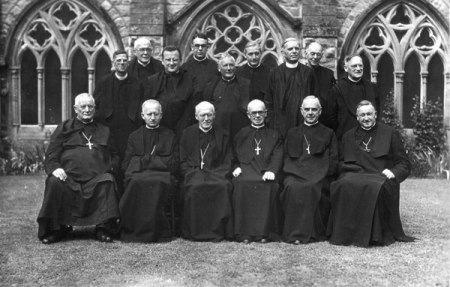

Benedictine Abbots and Priors, late 1940s.

Butler front second from left.

***

After the Great Fire of 1955 he presided over the most extensive building programme in Downside history, so incessant that direct labour by our own team of craftsmen rather than a contractor was employed. Around the original nucleus of the old college there began to surge up Ramsay, Ullathorne, the Theatre, the Gym, the Chemistry Laboratories, the New Classrooms, the Weld Refectory and the Monastic East Wing, culminating in the Monastic Library, at whose opening ceremony the assembled workmen were bemused by the quotations from classical authors which interlarded his oration. This was in spite of the fact that his recent appearances on radio and television, particularly in the programmes Brains Trust and Any Questions, had revealed an unsuspected capacity for communicating to mass audiences. In 1966, together with John Coulson, he launched the Downside Centre for Religious Studies, with the purpose of providing a Catholic presence in the Department of Theology at Bristol University. This brave venture required unlimited patience in the negotiations with the many different authorities concerned and equal persistence in soliciting the necessary funds from various foundations. But he was held to his purpose by the knowledge that it was well and truly in the spirit of Newman's The Idea of A University. This very delicately constructed work has not only survived but has ensured a constant stream of Catholic lecturers and several hundred Catholic students of theology in Bristol. It revealed also one of his outstanding characteristics, his openness to and trust in lay people, believing that they should have more than a passive role in the Church. In 1961, he was elected President of the English Benedictine Congregation, and it was by that chance that he would be summoned to the Second Vatican Council.

This was to be his finest hour, but at first the news filled him with no pleasurable anticipation: he feared it would be a tedious full-dress parade, reasserting what had already been asserted, but in a far more strident way. In the event he discovered that, to an extent unbeknown to him, theologians in France and Germany had arrived at positions, especially a vision of the Church, similar to his own, and were determined to make their views felt. From the first time he himself mounted the rostrum at the Council, he felt he had the mood of the audience with him. It has become a commonplace that Newman was 'the invisible father' at Vatican II, but to be Newman's spokesman probably no one in the assembly was better equipped than he. He was soon elected to the reconstituted Central Theological Commission of the Council which overhauled the original rather pusillanimous schemata for the Council decrees, and thus he played a direct and prominent part in ensuring that the Council's work would be creative and positive rather than reiterative and condemnatory. He himself was largely responsible, with help from Dom Ralph Russell, for getting the Council's treatment of Our Lady set in its appropriate theological context as a chapter inserted into the Constitution on the Church, Lumen Gentium, rather than as a separate topic. And he was especially eloquent that the fullest freedom be given to Biblical scholars. Few of the Council's participants could have done their homework so thoroughly. After the heavy morning sessions he would spend the rest of the day and night scrutinizing and amending the draft schemata. Not to waste time he declined all social invitations, and to keep the monastic pattern of his life he made a point of attending every liturgical office at Sant'Anselmo. The College buzzed with callers of every nationality, each more exotic than the last, come to confer with him. He had been discovered as the chief English-speaking contributor to the Council. His own sense of the occasion is best described in a letter he wrote to Canon Martin Hancock (2nd November 1962):

You know, one of the great blessings of my life was reading von Hügel. I suppose I might have got from elsewhere what in fact I got from him: a deep, clear, realistic insight at once into the imperfections and the necessity of the institutional element of religion. Yesterday, in spiritual reading, I was reading Matthew xxiii, the fearsome denunciation of the 'Pharisees and Scribes' - who nevertheless sit on Moses's seat and must therefore be obeyed. I suppose we in the Council are the scribes and pharisees of the present day. There we are, fettered by ignorance, error and prejudice; driven by ambition and human respect and plain fear and every kind of self-interest; with our enlarged phylacteries (you should have seen the mitre I borrowed for the plenary session!) and our deep rochet lace; bored and irritated and irresponsible - yet we sit in Moses's seat, Christ is with this two or three thousand gathered together in his name; and what seems good to us will seem good to the Holy Ghost; what we bind and loose will be bound and loosed in heaven. God draws straight with crooked lines; tous les serviteurs de l'iniquité sont les esclaves de la justice, et l'action divine batît la célèste Jérusalem avec les ruines de Babylone (can you place that quotation?) Meanwhile the real work of the Council is being done by the prayers of Christ's little ones and their unnoticed suffering.

His close acquaintance with the history of the Early Church had left him under no illusion that ecumenical councils settle everything. Rather they have almost invariably had contentious aftermaths, and their fruitfulnesses depends on the reception given to the conciliar teaching by the rank and file of the faithful. A cautionary example he sometimes cited was the rejection of the union with the Greeks achieved by the Council of Florence when the Emperor and Patriarch returned to Constantinople. He therefore made it his mission to communicate the conciliar vision to his English co-religionists who were perhaps of all the European churches the least prepared for it. But he soon discovered that his services were called for by an even wider audience. From Oxford he was invited to give to a crowded Examination Schools the Sarum Lectures of 1966 which were published as The Theology of Vatican ll. In that same year he was whisked away from Downside to be Auxiliary Bishop to Cardinal Heenan with whom, despite their differences of temperament, background and ecclesiastical outlook, he had many years of amicable co-operation. It would be interesting to speculate on the Cardinal's intention in requiring his services, but the outcome soon showed that many rather special commissions affecting the whole Church in England were entrusted to him. Nevertheless a strong and cherished local bond was wrought when he was assigned special pastoral responsibility for Hertfordshire. His installation as Area Bishop was celebrated in St Alban's Abbey, and his Anglican counterpart was Bishop Runcie whose own tribute in the Church Times was to be the warmest of all his obituary notices. He was President of St Edmund's, Ware, and Chairman of the School Governors. He made Ware his residence, and it came to take the place in his life that his monastic stability had once occupied. The ceiling above his armchair was black because of his pipe-smoke. The Head Master found him supportive and unobtrusive, the boys approachable and generous with his time.

In the national affairs of the Hierarchy ecumenical work became his special responsibility. Along with Bishop Clark of East Anglia he was the chief Catholic contributor to the breakthrough achieved in the agreements of the Anglican-Roman Catholic International Commission, a task which he found personally exhilarating because it bade fair to bridge the caesura in his own life ever since his conversion, as well as to fulfil his lifelong hope that the Anglican Church would be 'united but not absorbed'. For his services to the cause of unity he was twice awarded the Cross of St Augustine by the Archbishop of Canterbury. He also served as a member of the Archbishop of Canterbury's Commission for Church and State.

But his outreach did not stop at his former Communion. Towards the Free Churches he did not have the ready sympathy with their traditions and spirituality that he could summon up instantly for the Church of England. Scripture study was the common ground on which he befriended and respected the great Nonconformist scholars, H. H. Rowley and C. H. Dodd and others whom he encountered on the Editorial Board of the New English Bible. A still wider ecumenism came into play on the Social Morality Council whose President he was for many years Here he was engaged in building up a common front on moral values in public life, on drugs, broadcasting and particularly on ethical teaching in state schools, not only with representatives of the Christian Churches, but also with Jews and especially Agnostics. His love of rationality which had already qualified him for broadcast debates with Bertrand Russell and Freddie Ayer ensured a ready understanding with the representatives of the Humanist Association, Lord RitchieCalder and Harold Blackham who has written:

As one who did not share the faith of Bishop Butler but did share, as a colleague, one of his commitments, I learned to appreciate profoundly his fundamental simplicity, intellectual honesty, and honourable character. No one with his strong religious beliefs could have been less touched by bigotry, nor less doctrinaire. His thoughtful adherence to doctrine was qualified by the deeper moral conviction that what was not expressed in love could not be Christian. This made it possible for him to work whole-heartedly with others of a different persuasion, and for those others to work with him. This tempered humanity is his memorial that remains in heart and memory with his colleagues.

Bishop Butler gained from this experience: social concerns which had previously not generated any passion in him now began to exercise him, particularly the questions of nuclear deterrence and the rights of conscientious objectors. This time more like Manning than Newman, he began to appear on the doorsteps of Downing Street, heading deputations. That in the midst of all these rapprochements he had not slipped his moorings we can be assured by his appointment to the Congregation for the Doctrine of Faith, the re-named Holy Office or Roman Inquisition, where he served between 1968 and 1973, and by his receiving from the Pope the special honour of 'Assistant to the Pontifical Throne' in 1980. One of the paradoxes of his personality was that he was at the same time a conservative and a radical. The basis for this might lie in his own claim that he was a short-term pessimist, but a long-range optimist.

This Hertfordshire eventide was the stage of his life when he was happiest and most fulfilled, not only because, as he said himself, 'he no longer had to live with those he misruled', but because everything he loved and believed in seemed to be coming together at last. He was now an elder statesman in the Hierarchy. But enthusiasm and success which had previously been outlaws in his spirituality were now among its chief expressions. But it was not the case that he had outgrown Downside though as a bishop he had come to question the theological basis of both monastic exemption and the conjunction of the monastic state with the priesthood. Nevertheless the lineaments of a prayerful monk whose chief points of reference are very simple and direct were still discernible to all those who had any close contact with him. A young priest who had only just been appointed his secretary once gave himself permission to borrow the bishop's car for a visit to his former parish in East London. While he was there indoors, the car was stolen, together with all the bishop's robes and documents. He telephoned Bishop Butler and stammered out an explanation. The immediate reply was 'There is only one thing in life anyone should worry about, and that is sin. Go to bed and forget it.' Abbot Butler was one of God's great gifts to Downside, and was one of Downside's great gifts to the Church at large.

Ceredig.